African American History Tour in Chestertown, MD

1. Beginning in the late 18th century the waterfront area known as Scott’s Point was once home to a large free African-American population, many of whom owned their own homes. In the mid-twentieth century much of the Scott’s Point property was owned by African-American businessman Elmer Campher. Much of the property was sold in 1988 and upscaling began. Only a few of the older African-American homes remain on Water Street today.

1. Beginning in the late 18th century the waterfront area known as Scott’s Point was once home to a large free African-American population, many of whom owned their own homes. In the mid-twentieth century much of the Scott’s Point property was owned by African-American businessman Elmer Campher. Much of the property was sold in 1988 and upscaling began. Only a few of the older African-American homes remain on Water Street today.

2. In 1849 Isaac Boyer and Levi Rogers, Free Blacks, bought houses in Scott’s Point. Boyer, a drayman, bought the house at 210 Water Street. Rogers bought the house at 202 Water Street, that had been built c. 1740. Rogers, a former slave, operated an oyster-house there known as the Cape May Saloon. in the 1850s.

3. 104, 106 & 108 Cannon Street were property of Thomas Cuff. Born in 1785, Cuff was a prominent free Black businessman who bought the property at 108 Cannon Street in 1820 where he lived until his death in 1858. A highly successful entrepreneur, Cuff bought and sold real estate--especially in Scott’s Point--to both blacks and whites. In his younger years he operated a herring fishery on the Chester River. He was one of the founders of the African Americans’ Methodist church, originally located at 106 Cannon Street. Cuff is believed to be buried in the church’s old graveyard behind 106 & 108 Cannon St. Cuff bought and freed slaves, including some family members. His daughter, Maria Bracker, ran an ice cream shop at 104 Cannon Street. She was arrested for moving to Chestertown from Delaware, because Maryland law at that time prohibited free Blacks from moving into the state. She was released because the statute of limitations had passed.

4. The house at the corner of Cannon and Queen Streets, still standing but much renovated, was bought in 1796 by Henry Philips, a former slave. Philips used the building as both a residence and a store. By 1804, he had become the wealthiest African- American man in the county. In the 1960s-1970 it became Pood Lee Kates Corner Store. Also near there were Al Hart’s Bowling Alley, Pool Hall, and Laundromat and next to it Johnnie Stalon’s candy store on Queen Street. .

5. In 1882 William Perkins and 25 veterans of the Civil War organized the Charles A. Sumner Post #25 of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). They incorporated in 1908 and this hall was built by the Landing family and others, including Black Civil War veterans, some of them former slaves. It is one of only two such Colored Troops veterans’ halls still standing in the U.S. After the death of the last Civil War veteran in 1928, the building continued to be used as a social meeting place. In the 1930’s the Eastern Shore Club (Samuel McGreer, Earl Frazier, Leonard Johnson, Sr., and Leonard Houston, Sr.) held dances, promoted local performers and the national all girls band, the Sweethearts of Rhythm. In the 1940s they brought in the young Ella Fitzgerald and Chick Webb. They formed the Charles Sumner Beneficial Society for the purpose of helping fellow veterans and local families in need with medical and burial expenses. The wives and daughters formed an auxiliary society called the Charles Sumner Women’s Relief Corps (W.R.C.), a local branch of a national organization connected with the G.A.R. The traditional belief core of mutual help started with the Civil War veterans. In the Jim Crow era the Centennial Beneficial Lodge #9 Society met there, and with president Earl Frazier fought for civil rights for three decades. It was one of the few places where African Americans could socialize. The Centennial Beneficial Association owned the hall from 1950 to 1978, when the few surviving members sold the building to Elmer Campher as a church. It was restored by the Charles Sumner Post #25, Inc. and, as Sumner Hall, it serves as a museum, community center, and performance space.

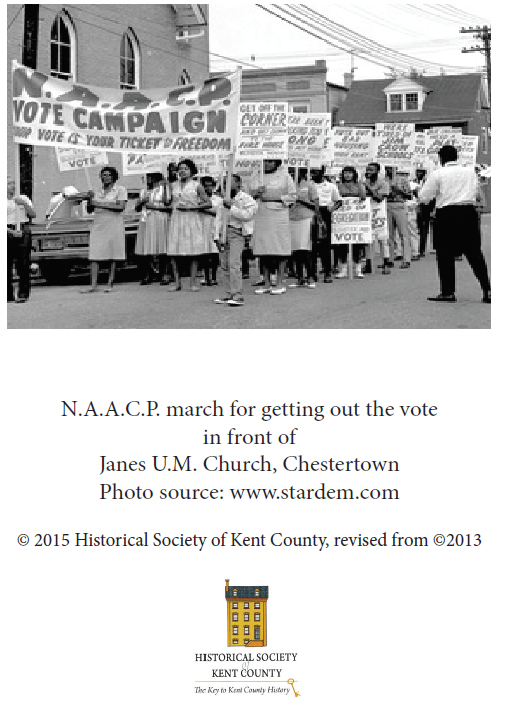

6. In 1831 local African Americans founded their own Methodist church. William Perkins and James A. Jones were among the founders. The church occupied two other buildings before the current structure named for Bishop Janes was erected 100 years ago in 1914 on the corner of Cross and Cannon Streets (#16). It was designed and built by mmbers of the church using hand-made concrete bricks. Today it is Janes United Methodist Church, whose presiding pastor is Rev. Candy Miles.

7. For much of the 20th century, the 300 block of Cannon Street was home to a variety of thriving African-American businesses, including Joe Lewis’s corner store, Charles Smith’s restaurant, Harold Jones’s barber shop, Buzz Johnson’s barber shop, Frazier’s barber shop, Francis Martin’s laundry, Lucille Warren’s beauty salon, Jen Philip’s beauty salon, Elijah Smith’s Tavern, Sam Hoxter’s Tavern, Claire Jackson’s candy store, Wright’s Restaurant, Commodores’s Electric, Clark’s dairy store, LeAnne Blake’s church, Hunter’s Bar and the Brite Printing Company.

8.-9. James A Jones, a grocer, butcher, tavern-owner, and money-lender, was one of the most successful 19th century African-American businessmen in Chestertown. In 1871, Jones sold a single square foot of land at Cannon and Mill Streets (#8) to fifty local African American men for a total price of five dollars, in order to get around Chestertown’s property requirement for voting. Other landowners made similar sales in other years. As a result of their efforts, dozens of African Americans were enfranchised and the property requirement was eventually dropped. Jones’s house, which is no longer standing, was at the corner of Cannon and Kent Streets (#9).

10. Donald Strong’s gas station and garage in the 1960s-1970s.

11. Another Black neighborhood dating to the nineteenth century was focussed on upper Calvert Street and College Avenue. This is the site of Charlie Graves’s Uptown Club, a popular bar and dance hall of the 1950s and ‘60s that offered live music and attracted visitors from all over the eastern and western shores. Among the performers on the Chitlin Circuit brought to town by the Uptown Club in its heyday were BBKing, Fats Domino, James Brown, Etta James, Chubby Checker, Ruth Brown, Little Richard, Otis Redding, Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, and Patti Labelle. Local bands included Jazz Johnson’s band and the Highlanders.

12. Formerly, the Gospel Church of God, presided by Bishop Fisher.

13. Site of the original Garnett School, a high school for African American students built in 1916 and founded through the efforts of Miss Emma Miller. The school was named for Henry Highland Garnet, a nationally and internationally known Black abolitionist who was born into slavery in Kent County. Prior to Garnett’s opening, schools for Black children had been held in churches or in one-room schoolhouses scattered throughout the county.

14. Dr. Lindsey Richardson’s house. He was the M.D. for African Americans from the 1940s on. He died in the 1980s.

15. Bethel AME Church purchsed the land where the church was built on January 15, 1878. Among the original trustees were William Floyd, a sailor, and David Blake, a laborer. The church has been a focus of uptown African American life. In 1962, Bethel’s pastor, Rev. Frederick Jones, Sr., invited the Freedom Riders to come to Chestertown and use Bethel as their base. Two busloads and several carloads of Freedom Riders arrived to rally in support of integration and other civil rights. Joined by some local people, they marched the length of High Street from Bud Hubbard’s whites-only restaurant to the waterfront. In spite of sometimes violent opposition, the Freedom Riders remained in Chestertown for several weeks. The presiding Pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church is the Rev. Robert N. Brown, Jr.

16. The old Henry Highland Garnett School was built inaround 1926. Elmer T. Hawkins was principal at the original Garnett and also of the new Garnett School from its opening in 1949 until his retirement in 1967.

17-18. Among the many Black owned and operated businesses that no longer exist were Munson’s Market (#17), Smitty’s Fish Fry, and Isabelle Young’s beauty salon (#18), which was in operation from 1949 through the 1980s, all on Calvert Street.

19. Originally this building was Kenneth Walley’s funeral home, which served the local Black community, The building is now owned by the Kent County Public Library.

20. Janes Methodist Church met at 222 Queen Street in Scott’s Point and then when the present church was built (#8) the house was used as the parsonage. More recently it was moved to this location, 222 Calvert Street, in the early twentieth century.

21. Site of the first Methodist Episcopal Church where in the 1700s both black and white parishioners once attended. It was the parent church of today’s First United Methodist Church, Christ UM Church, and Janes UM church (#8).

22-23. In 2015 were are only a few Black owned and operated businesses in Chestertown today: The Corner Print Shop (#22), Big Mixx’s Beautiful Beginnings (hair salon) and Jab Cab (#23), and Life of Cake on upper High Street (off the map).

24. The fire station stands on the former site of William Perkin’s Rising Sun Saloon, one of the most prosperous Black businesses in Chestertown. Beginning in 1857, Perkins served Black and white customers at the Rising Sun for about thirty years. Nearby was Perkins Hall, built by Perkins as a meeting site for the Black community.

24a. Across the street where Royal Farms is now, was Walter Wickes’s garage in the 1960s. This area around Maple Street and Cross Street/Philosophers Terrace down to Queen Street was an African American neighborhood that no longer exists. Blackwell’s store was a Black business on Church Alley.

25. James Taylor, accused of a crime but professing innocence, was never able to have his day in court. On May 17, 1892, a gang of unruly white men broke down the door to Mr. Taylor’s jail cell and he was cruelly lynched on the courthouse lawn. The Baltimore Sun reported that black citizens planned a peaceful protest by agreeing to boycott any white businessman who was involved in the conflict.

26. Monument to Colored Troops of Kent County in the Civil War. By the 1850s there were more free than enslaved African Americans in Kent County. Over 400 Blacks in Kent County, many of them slaves, joined the Union Army. Under Commander Calvin Frazier, the Parker White Post of the American Legion was instrumental in getting the Civil War monument erected in 1999.

27. The Prince Theatre at the Garfield Center for the Arts was the first movie theatre in Chestertown. Originally named the Lyceum, the theatre was segregated from its opening in 1928 until the early 1960s with Blacks only allowed to sit in the balcony.

28. Wide Hall, 101 Water Street, was built in 1769 for Thomas Smythe from whom Henry Philips (#4) purchased his freedom in the late 1700s.

29. The Custom House, once the home and offices of Thomas Ringgold, a merchant, attorney, and slave dealer, is now owned by Washington College. Tours are available here.

The African American Community History Project of the Historical Society of Kent County produced this map with assistance from the Diversity Dialogue Group of Maryland. and the Kent County Arts Council. Created by Armond Frazier Fletcher, Jane Jewell, Lucy Maddox, Milford Murray, Jeanette Sherbondy and George Shivers. Revised September 2015.

Look for our other publications, exhibits and events on Kent County’s African American History. Access our HSKC website at kentcountyhistory.org. On Face Book we are Kent County Historical Society. Email: Director@kentcountyhistory.org and phone: 410-778-3499 You are invited to bcome a member of the Historical Society! Visit our Bordley History Center at 301 High Street for more exhibits and resources for family research. Open Wed-Sat. from 10 am -3pm.